Climbers currently preparing for Makalu and Lhotse will want to look closely at the reports just published by 8000ers.com. The detailed information may ensure that when climbers stand on what they believe is the summit, that they will actually be there.

The late Iñaki Ochoa once said that the top is the point where everywhere else is down. Notwithstanding the clarity and accuracy of Ochoa’s definition, things are less simple in practice. If all the summit claims on Makalu, Lhotse, and the rest of 8,000ers underwent strict scrutiny, the results would be a “bloody mess”, according to Rodolphe Popier, author of most of the reports (except for the one on Manaslu, by Tobias Pantel).

Rodolphe Popier.

‘Tricky’ summits

The France-based Popier has worked for years investigating hundreds of summit claims and thousands of purported summit pictures. Part of the team at both The Himalayan Database and 8000ers.com, Popier is highly skilled at identifying topographical features, including ridges and boulders. He then registers their reappearance in photos, even under different conditions, and draws conclusions accordingly.

Makalu. Photo: Mike Horn

In 2012, mountain scholar Eberhard Jurgalski asked Popier for help checking some unclear summit claims on the sometimes ambiguous summit of Annapurna. The collaboration worked. Since then, the pair have melded accounts, photos, maps, satellite images, and GPS trackers into hyper-detailed reports of the upper sections of Annapurna, Manaslu, Dhaulagiri, Broad Peak, and now Makalu and Lhotse.

The late Piotr Morawski on the main summit of Shishapangma, during the first winter ascent with Simone Moro. Central summit behind. Photo: Simone Moro

“Some decades ago, the tricky 8,000’ers were supposed to be Cho Oyu, with its huge summit plateau, Shishapangma with its central summit, and Makalu with its foresummit –- the summit actually lies at the end of the sharp, exposed final ridge,” explained Popier. (Makalu is similar to Manaslu in that way, although its final bit is not as difficult.)

“However, as the number of summiters and testimonies increased, it became apparent that many climbers also did not reach the highest points on other 8,000’ers.”

Ultimate proof

Technology has, of course, improved their job a lot. The new trackers have certainly helped. “But especially the internet and Google Earth,” says Popier. “Without [them], nothing would have happened.”

Popier admits that last year’s drone footage from Jackson Groves showing the real summit of Manaslu was “a dream come true”. His photos clearly showed a small number of climbers either on the summit or moving toward it, while most queued for their photo op on the foresummit, which was significantly lower.

Jackson Groves’ drone footage shows climbers queuing at Manaslu’s foresummit, while the Imagine Nepal team traverses on the right toward the main summit. Photo: Jackson Groves/JourneyEra

Climbing audiences applauded the images, which put the whole Manaslu summit/foresummit debate to rest once and for all. At the same time, it came as a bitter surprise for hundreds (!) of previous climbers. Should they now strike Manaslu from their list of accomplishments or return to bag the actual summit?

Rewriting history?

Prior to this episode, the summit of Manaslu presented a wicked dilemma for the 8000ers.com team. Although it was hard to verify all past summits, an overwhelming proportion of them had stopped short. “We would have virtually destroyed the history of mountaineering,” Popier said.

He added: “Trapped between total tolerance and rigor, we first agreed to accept points close to the highest points via the ‘tolerance zones’ concept. It was an intermediate, diplomatically acceptable solution to avoid bloodshed.”

The drone footage clearly shows the Manaslu summit area, including the point where nearly all climbers stop, and the real summit to the left, at the end of a spiky ridge. Photo: Jackson Groves/JourneyEra

The Manaslu debate

Last autumn’s Manaslu photos eventually led both institutions of high-altitude chronicling — The Himalayan Database and 8000ers.com — to take a more stringent position.

“The HDB chose to declare an amnesty for all past climbs but to accept no more ‘foresummits’ from now on,” said Popier. “It is, in my opinion, the most diplomatic choice.

“The second option is what Eberhard decided to do, which is the best option for the sake of historical truth: to delete the [proven] ‘foresummiters’ from the list.”

As Jurgalski added, “Yes, it changes history, but better changed than just wrong.”

The detailed reports for Makalu and Lhotse are sometimes difficult to read, but they are definitely worth studying. Most of all, for would-be future summiters.

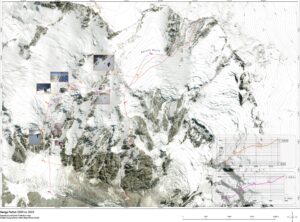

Makalu summit area with features compiled by Popier/8,000ers.com on a photo by Summitpost.org.

On Makalu, climbers reaching the top of the so-called French Couloir glimpse the foresummit at the end of a long snowy shelf. Only from that point are they finally able to spot the real summit pyramid.

Makalu’s summit sections marked by 8,000ers.com. Photo: Elisabeth Revol

On Lhotse, some climbers have taken their summit pictures at the end of the characteristic West Couloir. However, from there, they must turn left and climb a rocky edge until the corniced summit slab. Both the slab and the cornice (sometimes too fragile to step on) are considered the summit.

The upper sections of Lhotse, with some climbers on the West Couloir. Features added by 8000ers.com. Photo: Grand Himalaya Expeditions

It is worth noting that Jackson Groves and his drone will be climbing Makalu this spring. We hope that he sets his bird aloft again, although it’s rare for a drone to hover above climbers’ heads at 8,000m.

Why is proof of summiting necessary?

What actually prevents a climber from claiming a summit without solid proof?

“Mountaineering is not a regulated sport, with video replay and referees,” Popier admits. “It is a voluntary activity done for personal reasons, and every climber is free to tell or conceal whatever they deem adequate. [We] try our best to keep track and compare reports and pictures, when they are available. But we cannot force anyone to provide proof of an ascent.”

He points out that the opposite also happens: “Climbers have completed some remarkable achievements but decided to keep them quiet, because they did it just for themselves. For example, Peter Riemann’s winter solo ascent of Cho Oyu SE Face, back in winter 1992-1993. He climbed without a permit, without proof or witnesses…I only knew of it years later.”

Above, Ferran Latorre on the summit of Makalu in 2017.

Nowadays, few climb prestige peaks “just for themselves”. Everyone works social media as their own public relations agent. Yet the climbers’ inspirational posts often lack factual reports, accurate data, and descriptive pictures supporting their summit claims. Again, this is secondary for those without professional ambitions, but it is significant in the case of sponsored athletes or those pursuing some kind of record.

Prove and you won’t be judged

“The only thing that we and especially the media can do is encourage climbers to provide evidence,” said Popier. He refers to summit pictures with references, including other teams, GPS tracks, pictures of watches showing coordinates, altimeters, and time, and detailed reports of their summit day.

“Climbers must understand that by providing all that info, no one will doubt their word. Otherwise, it will have to be us — other alpinists, researchers, the media, the audience –- who will judge them, whether they like it or not.”

Luo Jing of China on Lhotse’s summit ledge. Photo: 8000ers.com

Unfortunately, there is not one overarching authority in the climbing community to evaluate summit climbs.

“Not the Himalayan Database, not 8000ers.com, not the AAJ, not the PO, not the UIAA,” says Popier. “And honestly, I don’t think there will ever be such entity, mainly because no one wants to bear the responsibility.”

That, he adds, is why climbers should at least document their own climbs, both to eliminate doubt and “to be respectful toward the culture they aim to belong to.”